A Closer Look at Two Underrated Watches With Calibre 11, the Hamilton Chrono-Matic

Cool chronographs, often forgotten, but still pretty spectacular.

The Calibre 11, or Chrono-Matic (depending on the brand using it) needs no introduction anymore. It is, with its two competitors, the Seiko 6139 and Zenith El Primero, amongst the most important movements ever created. Why? Because it was part of the earliest automatic chronograph movements launched in 1969 and celebrating its 50th-anniversary last year. Surprisingly, people often think about Heuer when talking about the Calibre 11, and sometimes Breitling. Less regularly though, the name Hamilton is mentioned. And today, we’ll look at how the Calibre 11/Chrono-Matic influenced a series of cool chronograph watches at Hamilton.

For more details about the Calibre 11, you can read this in-depth story here, retracing the origins of the consortium and the technical details.

The Hamilton Watch Company of Lancaster, Pennsylvania was America’s largest pocket watch producer at the turn of the 20th century. Indeed, close to half of America’s train engine drivers and railway workers – who depended on high levels of accuracy from their watches – were using them daily. As movement designs developed and tooling was created for case manufacture, the company slowly moved into wristwatches. Sizing down from their standard 50mm pocket watches to 28mm elegant wristwatches was no mean feat but, by the end of WWI, they had started setting the standard for American-made wristwatches.

Hamilton wristwatches stunned the world in the 1920s & 1930s with their Art Deco style, models like the ‘Piping Rock’ with articulated lugs and enamelled bezel, or the ‘Traveller’ with its twin-movement to display travel and home time. During WWII, Hamilton switched to military production only and supplied the US ARMY from 1943 with the troop-issued ‘hacking’ field watch. Always looking to modernize production, after the war, Hamilton designed the first Electric movement (in partnership with General Electric) creating a line of Hamilton Electric watches with the most famous being the Vega, the Pacer and the Ventura, the latter worn by none other than the King himself, Elvis Presley.

In 1966, Hamilton acquired the Buren Watch Company, a movement manufacturer in Biel, Switzerland. From 1966 to 1969, US-based Hamilton Lancaster and Buren Switzerland were jointly operated. By 1969, the Hamilton Watch Company terminated American manufacturing operations and closed its factory in Lancaster. From 1969 to 1972, all new Hamilton watches were produced in Switzerland by Buren, which later returned to Swiss ownership. By 1972, the partnership between these two brands was dissolved. In May 1974, the Hamilton brand was acquired by SSIH, or what would later become the Swatch Group – Hamilton’s current owner. However, Buren’s ownership proved to be crucial for Hamilton, but also for a group of the company, in order to create the 1969 Calibre 11/Chrono-Matic movement.

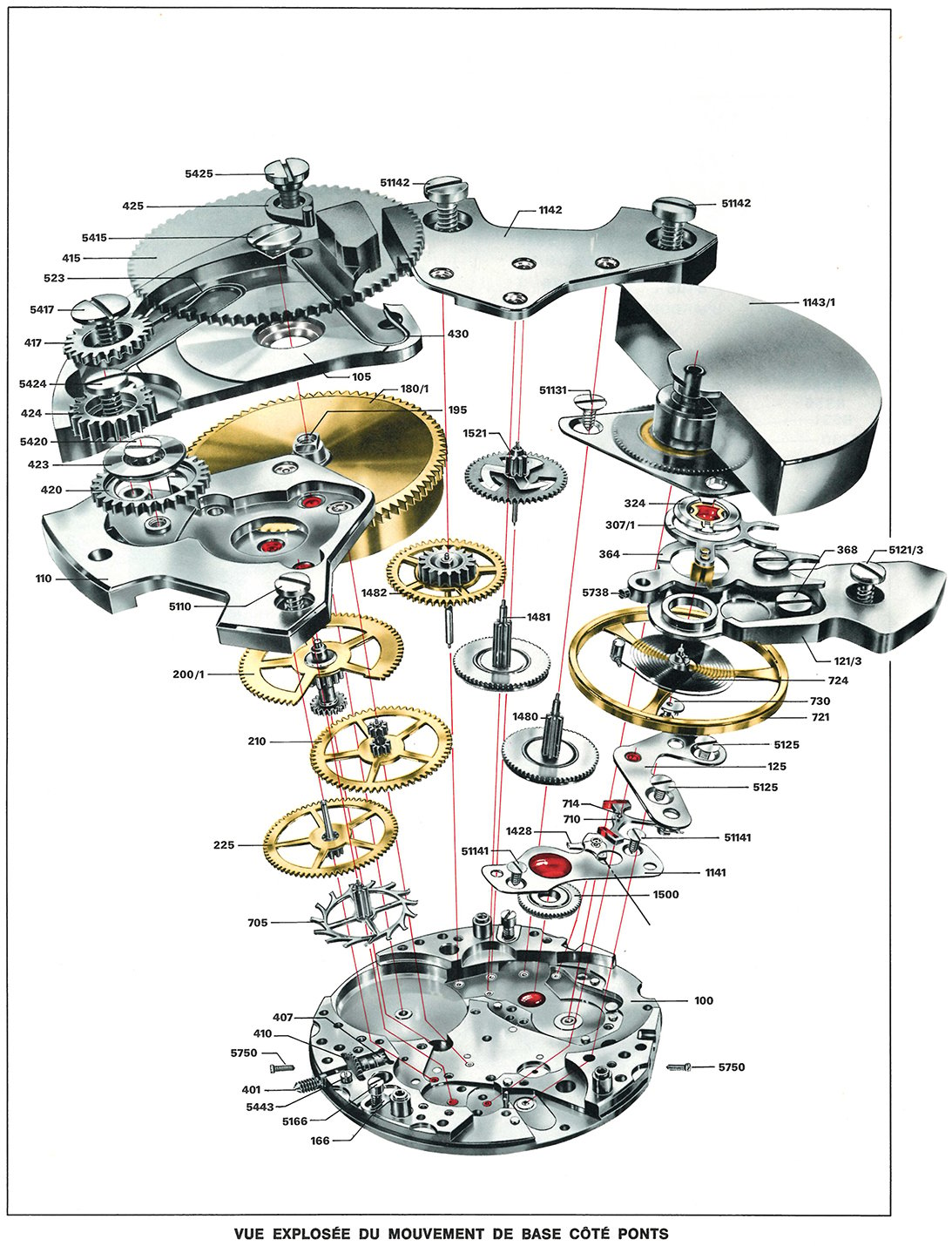

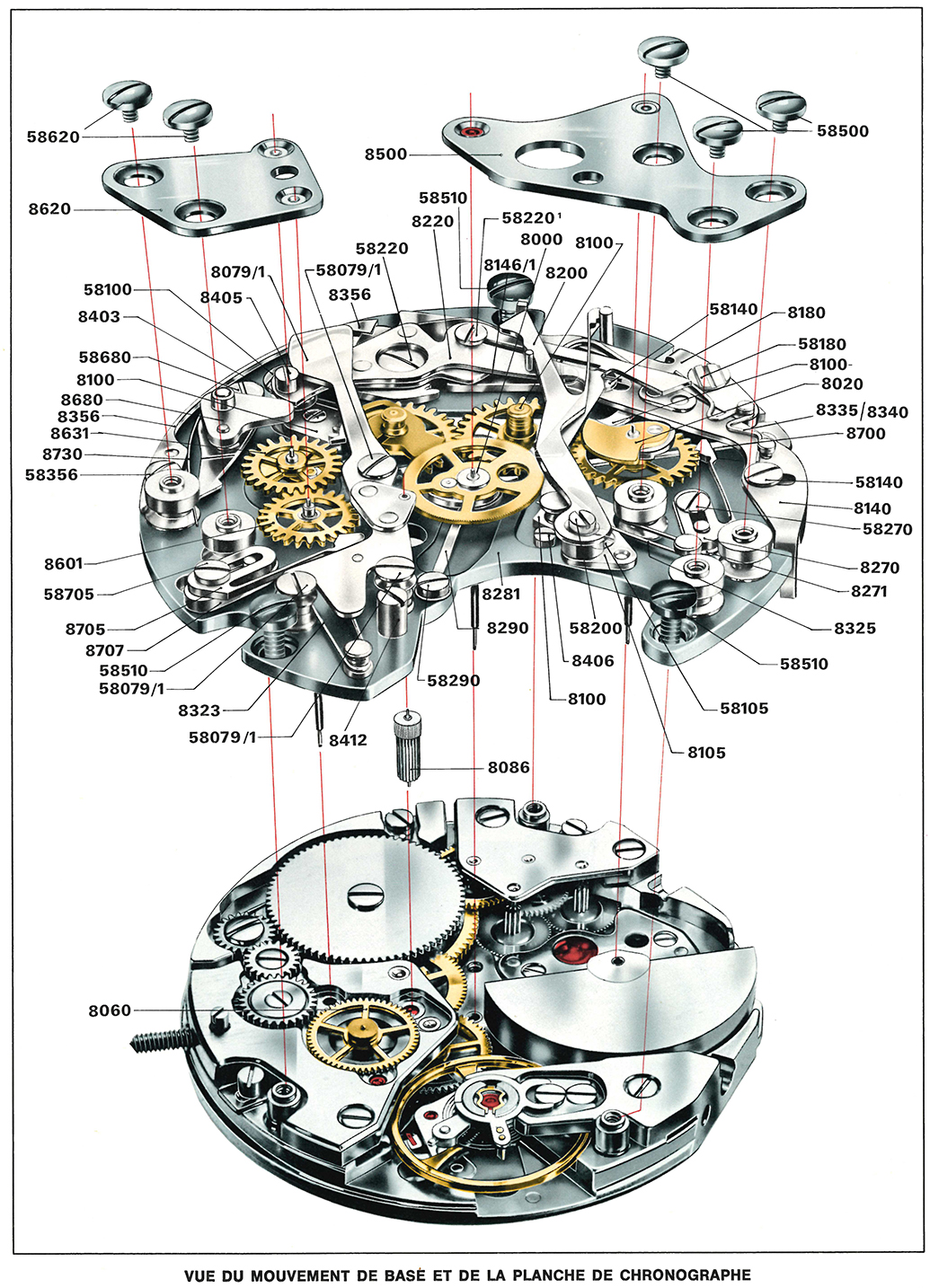

Hamilton returned to mechanical innovation in partnership with several other companies in 1966, with the so-called Project 99. That was the code name given to the development of an automatic chronograph movement, a joint project involving Heuer, Buren, Breitling, Hamilton and Dubois-Depraz (Hamilton became involved after their acquisition of Buren). As early as 1959, Heuer was already looking at several movement manufacturers to find a suitable automatic base movement on which a chronograph module could be fitted. It was not until Buren launched their thin micro-rotor automatic calibre 1280 that the project seemed feasible.

This Buren calibre was thin enough to become the timekeeping base, but the joint venture had to find the right supplier to manufacture a chronograph module to sit on top and be small enough to keep the movement from being too thick. This was the time of the Madmen-referenced slim watches, the Thino-Matic, the Electric Ventura and the Future-Matic watches. The task was given to Dubois-Depraz, a company specialized in turning base movements into complications, including chronographs. The development of this chronograph is a long and complex story… and we will visit it again in the Vintage Corner.

Today, I would like to look at a pair of watches that aren’t often mentioned. Although the idea with Project 99 was to create a thin movement, the joint venture didn’t quite achieve its goal – especially compared to the competition, Zenith and Seiko.

In return, what the larger movement did spawn were some very interesting and creative case designs, the two early Hamiltons here show the two ends of the micro-rotor design spectrum. They are both equipped with early Calibre 11, which was the first designation for these micro-rotor chronographs and they are both signed ‘chrono-matic’ on the dials – the name given by Hamilton to these movements.

The first of these two watches is the Pan-Europ, whose case design leans to the more exuberant side of the micro-rotor watches. To disguise the height of the movement, the case has been sculpted from a wide cushion-shaped base. It relies on a radial brushed finish to fool the eye and to allow the central part of the case (bezel and dial) to be the main focus. This is a technique used by a number of Heuer models, to somehow hide the true height of the watch into a ‘two-tier’ visual piece of magic. For the wearer who looks down on the top of the watch, the largeness of the case falls away like a ski slope leaving just the dial and bezel to consider.

The dial plays tricks again with raised baton markers, recessed chronograph counters, two internal rings – one for central seconds and the other is a tachymetre – combined with geometric baton hands – all in all a feast for the technical eye. The bezel is very thick, with wide notches for grip but also to break up the continuing lines. The bezel is partly recessed into the case, which also hides some of the depth and thickness with the thick acrylic crystal rounding out the top. This has a slight dome to it, which continues this theme of altering visual perspectives and overall gives the mind a lot to think about, drawing the eye away from the fact that this watch is a big piece of steel and at the time must have been double the height of a standard automatic wristwatch.

Conversely, with the second Hamilton Chrono-Matic, the designers went for a completely different approach, which appears fairly conventional at first. One of the issues that the designers had to deal with was the odd position of the crown on the opposite side to the pushers. Most of the hand-wound chronographs featured the crown and pushers on the same side of the case.

This watch, the Hamilton Chrono-Matic ref. 11002, features a solid matte blue dial, narrow markers, sleek sub-dials while continuing this theme with the thin stick hands and a bright inner flange with tachymeter scale, making this watch the total opposite of the much more complex Pan-Europ model.

With this less sporty but still classy looking incarnation, the designers sought to lose the height by bevelling the case edge on the top half and having the crystal stand up from the case with a solid curved edge, leading to a thinner dome across the face. The lugs are quite thick and are angled at 45 degrees, so visually, from above the case resembles that of the standard hand-wound Hamilton chronograph already produced. Unlike the Pan-Europ, the trick to visually hide some the thickness of the movement is done through the caseback – in fact, more of a cap, at about 5mm deep, with its edges bevelled or rounded. Still, this version of the Hamilton Chrono-Matic remains a hefty watch with a lot of steel visible on the caseband.

Both of these designs are very clever in concealing the true height of the Calibre 11 movement. I wanted to pay tribute to the designers involved in Project 99 who came up with the designs that made these watches so iconic. When you look at many watches from the early 1970s, you can see cues from the designs chosen by Heuer, Breitling and Hamilton to accommodate their ‘new world movement’ and great credit should go to the project leaders from these brands who gave the designers such latitude and freedom to go ‘their way’, to create some very special watches. Hamilton has since reissued both of these watches, which are pretty faithful re-editions of the original models… Apart from the fact that the chronograph pushers and crown are on the same side of the case. Too bad…

1 response

Nice piece! One of my most beloved watches is a 7750 based “LL Bean” chronograph (with Hamilton markings)… I saw one in 1987/88 and wanted one. I had to wait 30 years to find a NIB piece. I cherish that watch.